Love is often spoken of in grand, romantic terms, and we can miss out on some of its most enduring expressions. On the occasion of Valentine’s Day, our member Ms R. Mukherjee reflects on the boundless gratitude love can inspire.

Love comes in many forms. It goes far beyond romance. I have a story of a love rooted in care, courage, and gratitude.

I grew up in a large joint family with seven siblings, and we were deeply affectionate toward one another. Yes, we were mischievous and would occasionally snitch on each other, as siblings do, but we also stood by one another whenever anyone was in trouble.

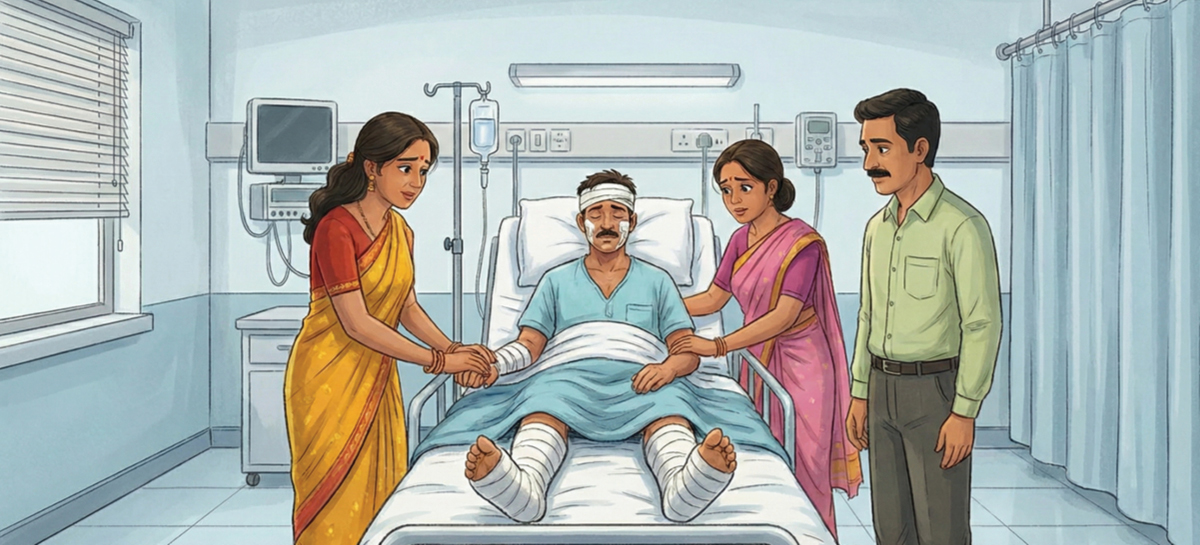

My Mejda, one of my elder brothers, was our greatest source of support and strength. He had a wonderfully generous nature. He later held a senior post in Delhi. One early morning, while commuting to a meeting, he was knocked down by a school bus. He suffered severe brain injuries and multiple fractures in both legs. It was remarkable how the entire family rallied around him. For the next five to six years, we ensured that his family in Delhi never lacked support. His two young children were surrounded by love and care.

His recovery continues to inspire us. His condition was so critical that the doctor refused to administer anaesthesia for surgery and instead placed his legs in plaster. The trauma to his brain was so severe that he could not recognise us. During that difficult period, our eldest brother, my mother, my husband, and many others travelled to Delhi to assist the family. We believe the love he received from all of us hastened his recovery. Despite medical scepticism, he eventually managed to stand on his feet again. Though he could never walk properly, the fact that he could walk at all felt miraculous.

Once he regained mobility, his gratitude overwhelmed us. Through both small and grand gestures, he expressed his love. I once casually mentioned that I admired a quilt from Jaipur and hoped to buy one someday. Soon after, he travelled to Jaipur and brought one back for me. For a man who could barely walk, carrying a quilt from Jaipur to Kolkata was no small effort.

What is the essence of such a gesture if not love? To me, love defies categorisation. It cannot be measured by material gifts. Love that inspires more love is the truest love of all.

(as narrated to Support Elders by our member)

Categories

The Measure of Love